Custom building a trailer from scratch seems like something that anyone can do – with enough time and space, of course. You build a frame, weld it up, you attach some axles, screw on a deck and bam! You’ve got yourself a trailer. Where it gets tricky is in the math behind load capacity. If you don’t do it right, you’re likely to experience issues ranging from the trailer failing inspection to wheels coming off on the highway.

Where people fail, unfortunately, when it comes to trailer capacity is thinking about it as a single number. They see 3,500 lbs stamped on an axle and assume that’s how much they can carry with that trailer. That’s not how it works.

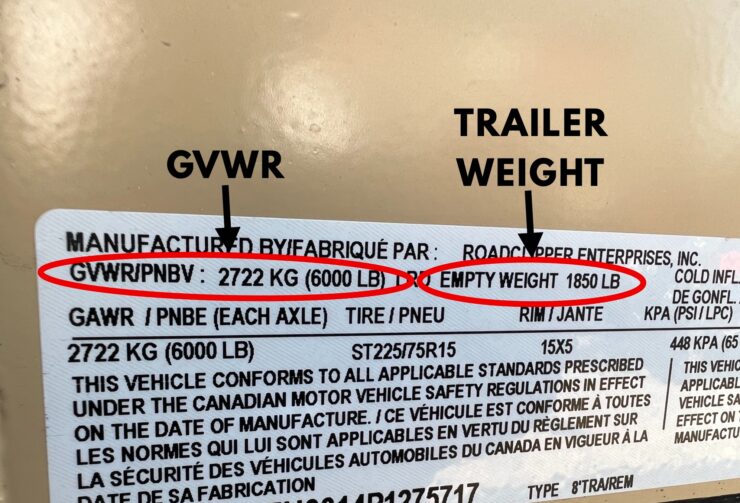

Gross Vehicle Weight Rating (GVWR)

GVWR is the maximum weight that a trailer can safely carry – which means everything. Frame plus deck plus wheels plus load plus spare tire that’s probably bolted on underneath. Most builders fail to realize this and are shocked when their “2,000 pound capacity” trailer can only haul 1,400 pounds worth of cargo.

Think about it. A 3,500-pound axle plus an empty trailer weight of 800 pounds equals 2,700 pounds worth of cargo capacity. Simple enough. But then you start throwing things into the mix. A toolbox made from aluminum? 50 pounds. Heavy duty ramps? 60 pounds. Angle iron for side rails and stake pockets? 40 pounds. Even essential spare parts like an extra hub or set of wheel bearings add weight you can’t ignore. Before you know it, you’re basically at 3,000 pounds after your additions alone.

The math is as follows: GVWR = axle rating(s) + trailer weight + payload. To make this work, however, each calculation needs to be estimated – there is no guessing involved. Find out how much your project weighs using a truck scale or a scrapyard that has a certified scale. For only components, a bathroom scale will work well enough.

Understanding Axle Ratings

Axles have specific weight ratings; however, those weight ratings presume proper installation and maintenance. A 3,500 pound axle has certain tire specifications and expectations for tire pressure – if they remain underinflated or not correctly rated, for example, the weight limits mean nothing. Proper lug nut torque and bearings that won’t seize are also critical.

A single axle trailer is only rated for the amount of weight its axle is rated for. A tandem axle (two axle trailer) does not support twice the weight, either; it’s essentially two ratings total together – so if each is rated for 3,500 pounds, the maximum for that trailer is 7,000 pounds total. However, if one axle receives more weight than the other due to suboptimal placement once finished, the lowest axle becomes the limiting factor.

For custom builders serious about making their own trailers from scratch, the right DIY trailer plans can help avoid guessing with axle placement mistakes. A few inches can make the difference between a good fit and disaster.

Triple axles see the same thing occur; however, many jurisdictions don’t account for middle axles as full axles in GVWR determinations as they assume less weight travels over them since they become more used during turns. Check with your local laws before assuming you can just add up all three axle ratings together.

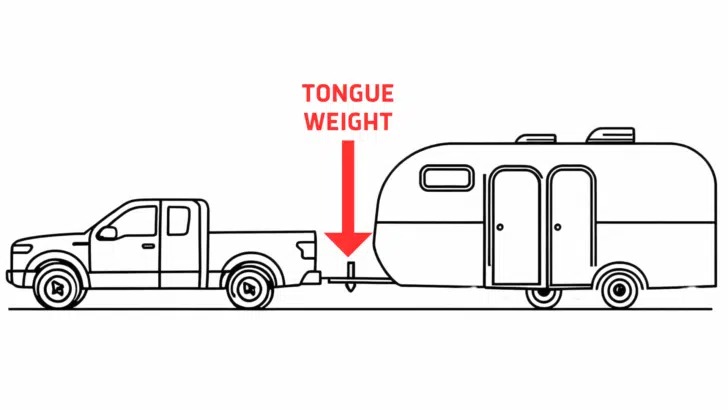

Tongue Weight

Tongue weight – what pushes down on the hitch ball – should be between 10% and 15% of the total weight of the trailer on the front end; too little tongue weight creates porpoising (trailer sway) at highway speeds; too much tongue weight overwhelms the rear axle of the tow vehicle.

This makes capacity complicated, because if you can’t position weight properly inside of the trailer deck, then it means nothing at all. For example, if a trailer has a 2,000-pound capacity but someone loads it entirely behind the axles, generating 5% tongue weight, then it’s meaningless because there’s not enough safety percentage.

To check this, multiply loaded trailer weight by .10 (minimum acceptable) and .15 (maximum). A loaded trailer of 4,000 pounds means that there should be between 400-600 pounds on the tongue for safe operation. Ideally this can be gauged through a tongue weight scale or bathroom scale positioned underneath the coupler jack.

The easiest way to adjust tongue weight is by adjusting loads and axles; changing where you put things inside the trailer is easier than moving axles three miles away from where they were supposed to be in the first place.

Weight Distribution Across Trailer Frame

Point loads vs distributed loads – this matters more than people know. An axle may hold 3,500 pounds but if someone focuses a load on one point area weighing 2,000 pounds against it, it’s going to bend frames and crack welds.

A trailer frame needs cross members and adequate bracing to account for weighted distribution throughout its structure. The type of decking material plays a role as well – a 3/4 inch thick plywood piece across the entire body distributes load better than two 2×6 boards running lengthwise because it’s more continuous.

Steel frames allow for more point loads than aluminum but also weighs down payload capacity – but unless larger axles are used to counteract this “weight penalty,” it significantly brings down payload capacity.

Buffer Factors Beyond GVWR

Running at capacity legally means that you have no choice – but so much can go wrong if you’re at your capacity with no safety margin. Brakes wear faster at max capacity; bearings become overheated; tires run hotter; any margin of error based on miscalculation can mean disaster.

Seasoned builders try to work with about 80% of what they think is their maximum – the maximum expected for that specific size predicted to learn – meaning that a “3,000 pound” rated trailer should be limited to a maximum working “2,400” pounds poundage for its life without issue unless problems arise due to normal wear and tear or things like gasoline in mowers taking up unwanted space.

Weather matters as well – a loaded trailer may handle no issue on dry pavement but if it fails on a corner due to excessive braking on wet roads or maneuvering during extreme weather conditions (pulling into traffic too quickly), it renders capacity obsolete overhead.

Gauging Upgrades

Addition sides mean additional cubic dimensions but also additional weight translates into how much wind blows against what’s loaded inside; enclosed trailers boast even more surface area for wind resistance which means reduced safe highway speeds and stability.

Upgrading tires help – but axles must support this upgrade. Going from bias ply to radial tires at higher pressure ratings means heavier work can be carried – but only if you have structurally appropriate axles tubes/springs/brakes that tolerate those increases.

Brake upgrades are necessary within trailers carrying extra capacity because most jurisdictions require them on trailers over 3,000 pounds (GVWR). It doesn’t matter whether this is required or not – trailers carrying serious loads need braking power beyond what their tow trucks provide.

Final Thoughts

Start with weights – find your weights over time. Weigh your frame materials before building and compound what’s added along the way without guess work. Go from estimates published for axles/wheels/tires instead of guesswork.

Calculate theoretical GVWR based on what’s expected from axle ratings; subtract what’s weighed as empty; what’s left means real cargo capacity – and it’s likely less than expected.

Test tongue weight from various placements before confirming an axle location; adjust while it’s still easy to modify.

Document everything – some states require engineered certification when building trailers by hand; even if this isn’t required it’s good to show your work in case inspectors bring up red flags where there are none.